After our two recent trips to Portugal, I became interested to see what remained of the more than 400 years of the Portuguese occupation of the state of Goa on India's west coast. So, in mid-July 2010, we set off by car from Bangalore to spend about one week in Goa.

MONDAY:

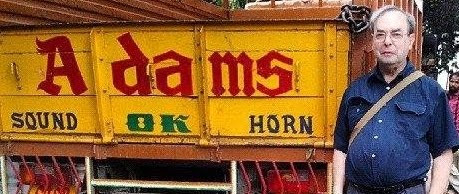

We set off at 5.30 a.m. in our Toyota Qualis driven by our driver, Rahim. Within an hour we had reached Nellamangala at the edge of the Bangalore conurbation. We sped up the National Highway towards Hubli in northern Karnataka. The road is good up to Chitradurga, but is under reconstruction between that town and Dharwar, just north of Hubli. The highway is four lane with a central divider (barrier), but this does not mean that all the vehicles on one side of the divider travel in the same direction! It is not at all uncommon to be in the fast, outer lane to find that a heavy lorry or an overloaded three-wheeler is approaching you from the opposite direction! Although stretches of the highway are subject to a toll, there is no shortage of road users who have certainly not paid, such as cows and oxen and their human keepers.

Up until Dharwar, the weather was good, and our average speed comfortably high (80-90 Km/h). At Dharwar we left the highway and headed westwards, and upwards into the Western Ghats, a mountain range that separates the Deccan Plateau from the the Arabian Sea coast. As soon as we began driving through the jungle-clad highlands, we encountered bad roads, and the rain fell in torrents. Our average speed dropped to much less than half what it had been earlier.

Near Castle Rock, we reached the Goan frontier. We were somewhat concerned when we read a notice that advised that cars with 'black' windows were not allowed into the state of Goa. Our vehicle had tinted windows. After Rahim had dashed through the rain and mud to the frontier 'check-post', a building that resembled an international frontier post, and might have been such a building before 1961 when Goa became part of India, he returned having paid the various taxes required to enter Goa. We continued our journey through the sodden forest, reaching Ponda well after dark. Navigation was difficult due to the poor maps and the darkness, but eventually we reached the town of Margaon. The traffic was terrible. After a few wrong turns we found our way to Colva beach, where we had booked into the Colva Residence, an establishment run by the Goa State Tourism Board.

This resort was built in the late 1960s, and is slightly shabby, but is excellently located. The door of our air-conditioned room opened on to a verandah with a view to the sea just beyond a grove of palm trees. Every night, the not unpleasant noise of the waves pounding furiously against the beach competed with the whirring of the air-conditioner and the sound of the almost incessant heavy rain. During our first few days, we had to make many complaints about a variety of problems, but after that the staff began to do what they were employed to do, and our stay improved. However, I would not want to stay at this place on a future trip to Goa!

TUESDAY:

We drove north from Colva to Panjim, the new capital of Goa. The original Portuguese capital of Goa was at Old Goa further up the River Mandovi than Panjim. We had breakfast at Kamat's restaurant, which serves only south Indian vegetarian food. Most importantly, establishments like this serve real south Indian filter coffee rather than Nescafé or espresso and its variants. Kamats is on the edge of Church Square which is dominated by a church with a white facade, which is at the top of an elaborate staircase resembling that which leads up the the Bom Jesus Church near Braga in northern Portugal. The Government of India Tourist Office is close to the church. I was given a number of useful tips about places to visit. After a brief visit to Singbal's book shop, staffed by a bevy of helpful young ladies, we set off for Porvorim.

To reach this small town it was necessary to cross one of the two parallel long road bridges across the Mandovi. At Povorim, we asked directions for 'Houses of Goa'. This is a gem of a museum housed in a very original building designed by the Goan architect Gerard da Cunha. He has rescued architectural features from many of the decaying buildings scattered all over the state and displayed them in order that the visitor can begin to understand about the nature of traditional housing in Goa. After we had looked at the museum, the guardian suggested that we met the architect. Mr da Cunha is a charming man. He strongly reccommended that we took lunch at 'O Coquero' in nearby Porvorim.

It was a good suggestion. O Coqueiro occupies two traditional Goan houses. For many years it has been well-known for its award winning cuisine, but smoe time ago it became even better known when the serial killer Charles Sobhraj was arrested there.

I ate pork vindalho, a pork curry cooked with palm vinegar. It was delicious as was the sea-food thali that my wife chose. The thali had a selection of small dishes containing such items as prawn curry, small fried fish, and a reddish liquid whose tate remined me of the Turkish drink called 'Salgam'. We asked about the reddish liquid and learnt that it was made from dried kokum (Garcinia indica) soaked in water with salt and a little red chilli powder. To accompany our food we were served pao, that is bread rolls. The Goans like to mop up their curry gravies with bread. I am now of the same opinion!

The village of Saligao is due west of Porvorim on the way to the coast. There, amidst the paddy fields stands the late nineteenth century church of Mae de Deus, a neo-gothic wedding cake of a building. High above the main entrance on the western facade there is an interesting stained glass window. The Madonna stands above a map of India (sadly, the glass is broken and the southern part of the map has disappeared). The church was pretty much deserted, but eventually we found someone who opened it up for us. The interior, kept in good condition, was not as interesting as those of the older churches that we were to visit later.

We drove further west until we reached the sea coast at Calangute. Despite haveing a fine stretch of beach, the resort town was highly commercialised in a slighly tasteless way, and overcrowded. After taking a drink at a hotel on the seafront we drove south to Fort Aguada. Built in 1612 by the Portuguese to protect Goa from the Dutch, this enormous fortress commands a good view of the estuary of the Mandovi. It contains an enormous circular tower, the earliest lighthouse to built in the Indian subcontinent. Part of the fortress, inaccessible to tourists, serves as a prison. This prison used to house political opponents of Dr Salazar's regime prior to India taking over Goa. We admired the walls and the views from them for as long as we could manage in the swelteringly hot humid air before returing to our air-conditioned vehicle.

After resting briefly at Colva, we took dinner at Martin's Corner, a highly reccommended restaurant in the middle of a palm forest near Colva. The meal we had there was less satisfying than the one we had at O Coqueiro.

WEDNESDAY:

After an unsatisfactory breakfast at our hotel, we drove through the rain from Colva to the nearby town of Margao. This place, the largest town in southern Goa, is rich in buildings showing the influence of the Portuguese. Not least amongst them is the 17th century Church of the Holy Spirit which overlooks a large rectangular square. Its white painted baroque facade. About fifty yards in front of the west end of the church, in the square, there is a tall white, elaborate crucifix. This arrangement was typical of all the churches we saw in Goa. We were able to locate someone who kindly opened up the church for us. Inside, we were able to see the well-restored baroque altar piece with its two side altars. As in many of the older churches the pulpit was also a gem of baroque design.

After refuelling in Margao, we drove inland, passing through the rain drenched countryside until we reached the tiny village of Chandor. This is dominated by a long building with a grand central entrance, the Braganza House, which dates back to, or before the 18th century. Formerly, a single residence of wealth Goan landlords, this home has been divided into two separate dwellings by two branches of the family who though living under the same roof never speak to each other! The west wing is occupied by an elderly descendant of the Menezes-Braganza family, and the east wing is occupied by a descendant of the Pereira-Braganza family. We visited the latter first. It is filled with antiques including furniture carved by Goan craftsmen in the eighteenth century. Its private chapel includes a relic of St Francis Xavier: his fingernail. Near to the chapel there is an ancient relic from the early history of refrigerators, a gas-powered American device - no longer in use. Many of the windows in old Goan houses such as the one we were visiting do not contain glass, which was not easily available in bygone times. Instead their frames are filled with thin overlapping slivers of oyster shell. This wing of the house as well as the other boasted of a huge long ballroom.

We were welcomed into the other wing of the house by Dona Aida, its nonagenarian resident, who had been educated both in Portugal and in France (Paris). We were shown around by her friend Judith. This wing of the house is maintained in better condition than the other wing, and is filled with priceless antiques, the copious remains of what must have been an unbelievably fabulous collection. Sometime during the late 1940s, the family living in this wing fell foul of Salazar's regime, and had to flee from the house at very short notice, leaving their in th care of the servants. When they returned more than fifteen years later, they found that the servants had run off with many valuable objects, but not all of them for at least two reasons. One, the ill-educated servants did not appreciate the value of the rare oriental porcelain and some of the furniture. The other reason was that a few days before the Portuguese police arrived, much of the silver had been taken to a jeweller for cleaning. The receipt for the jewellery was in the hands of a cousin who was not wanted by the authorities. She recovered the silver, and kept it safely until the family which had fled to escape from the police eventually returned.

We drove through the rain from Chandor to the small town of Quepem, and soon found the Palacio do Deao. This long single-storied building set amongst well-restored formal gardens was built more than two hundred years ago by the Portuguese noble-man who founded the town. This same gentleman built the church which faces the palace. The main entrance of the palace was, like that of the Menezes-Braganza House, in the centre of the long building. The door was open. We entered what seemed at first sight to be a deserted, but elaborately furnished, beautifully restored residence of some distinction. After a few minutes, we heard voices at one end of the house, and when we approached these we met a man, who was keen to show us around.

This man, the present owner of the palace, Ruben Vasco da Gama, a retired engineer, bought the Palace a few years ago. The building and its gardens were deserted and in ruins. Painstakingly, he and his wife, a biologist, researched the history of their new possession and buildings like it, even making trips to Portugal to do so. They used their knowledge to restore the palace and its gardens, the finest of their kind in Goa, with their own hands. Their labour of love has resulted in the restoration and conservation of one of the most magnificent examples of Indo-Portuguese architecture in Goa. And what is lovely is that the Vasco da Gama family use this place as their home. They are bringing up their children in a living historical museum.

'Vasco da Gama' will sound like a familiar name to most readers. No, Ruben is most unlikely to be of the blood-line of the great Portuguese explorer. When the Portuguese arrived in Goa, and no doubt elsewhere, they forcibly converted many of the local Hindus (mostly) to Christianity. The converts were given new family names. Batches of converts would be arbitrarily assigned the surname of the nobleman who converted them. Hence, the abundance of Goan names like Couto, Pinto, Menezes, Pereira, Braganza, Mascherenas etc.

Ruben recommended that we ate lunch at Pepper's restaurant in Margaon, which we did. It was a good suggestion. After eating, we drove through the rain-drenched country side in search of the seminary at Rachol. It was difficult to find because of an error on the somewhat useless map we had been given at the tourist office in Panjim, but after taking numerous wrong turns and asking many dripping people standing by the roadside, we found it, just in time to see about twenty white-clad seminary students heading down the hill upon which the institution is perched.

The seminary at Rachol was established as an institute for theological study in the sixteenth century. Most of its graduates become priests in Goan dioceses. This differs from the seminary we were to visit later at Pilar, where most of the students are trained to do missionary work amongst the tribal people of India and further afield, beyond India's borders. The doorman at Rachol asked one of the seminarian students to show us around the extensive premises. He gave us a thorough tour leading us along long corridors where the fathers and their students lived, into the elaborately decorated sixteenth century church, the television room, the recreation rooms, the refectory, and the large library with its many books and an extensive array of journals covering a wide variety of current topics. Our daughter remarked quietly to me that she noticed that 'Playboy' was not one of the magazines that the Library subscribed to! He explained that the training took nine years, and that some students boarded whilst others came daily from their homes.

That evening, we dined at Martin's Corner near Colva once again, not because we thought the food was good, but because our daughter wished to participate in the Karaoke show that was being held that evening. The singers had to compete with the sound of the heavy rain thundering on the corrugated iron roof and the frequent power-cuts caused by the rainwater short-circuiting the electricity supply!

THURSDAY:

It was not raining when I awoke. Whilst the others got themselves ready, I walked inland along Colva's main street. I passed shops with Russian signs (many Russians visit Goa), bullocks grazing in a field. Many of these had small birds perched on their backs whilst larger white birds followed them around on the ground. These white birds are often seen in the company of cattle. I reached Our Lady of Merces church by about 7.45 in time to see that a service was in progress. This allowed me to see the beautiful interior of the church, something we had been trying to do without success since our arrival in Colva. The church is next to a couple of schools. children were arriving and being lined up in front of their teachers in the yards outside the schools. The cross facing the church had a small plaque on its base informing that it had been financed by Goans from Colva who had settled in East Africa. Many Goans emigrate, but none of them lose their affection towards their homeland. Just beyond the church there were a number of women sitting by the roadside selling fresh fish, no doubt caught earlier in the day by their fisherman husbands.

On our way towards Mapusa, I spotted the white facade of a baroque church high upon a hill in the distance. We reached it by following a road which led to Guirim School. The church at Monte Guirim was not in our wonderful, detailed book by Maurice Hall ("Window on Goa"). So our curiosity was aroused. We managed to find someone to open up the church for us, and found that its interior was as splendid as most of the churches that our literary 'vademecum' recommended. We spoke with the church's priest who explained that the local laguage, Konkani, can be written both in Latin script, as it is in most of Goa's churches and in Konkani bibles, and in the Devnagri script in which Hindi is written.

Returning from Guirim to the main road, the National Highway number seventeen, we traveled further northwards and soon reached the busy hill town of Mapusa. With some difficulty we navigate our way through the town's narrow, congested streets to the large Milagros Church, another baroque edifice with a beautiful white painted facade dating back more than four hundred years. As with most of Goa's old churches, the facade was elaborate, as were the main altars and the pulpit. The other parts of these churches are relatively undecorated. The only part of the exteriors to be decorated are the west facing facades. In general the remaining parts of the exterior are made of undressed, unpainted, red coloured laterite (an iron rich rock typically found in tropical regions: it is easily cut into bricks sucha sa are used to construct Goa's old churches).

We entered the Milagros during the final minutes of a funeral service. As it ended the flower-strewn coffin was lifted from its position in front of the mourning, and to the accompaniment of much mournful wailing was carried out the southern door of the church. It was followed by a long procession of umbrella-bearing mourners.

After looking at the elaborate baroque artifacts in the church, we ventured out into the torrential rain, and continued our journey eastwards to a the house of a friend who lives in a place near to the village of Moira. We had lunch with our friend in her tastefully restored family home, before returning to Moira, where we looked at its church. Nearby, overlooking a river, near a place called something like Chicherim there was a ruined fort. A path led to its entrance but the dampness underfoot killed our enthusiasm to take a close look at it. We drove westwards to Panjim where we took tea at its oldest hotel, the 'Mandovi'. Built in 1952 to house the senior governmental and diplomatic visitors coming to see the exposure of the miraculous body of St Francis Xavier, it was Goa's first real hotel. Much of its original decoration has been carefully preserved including the elaborately stuccoed dining room with its complicated carved wooden window shutters. We decided to spend the last night of our Goan trip at this magnificent relic of Portuguese elegance.

On our way back south towards Colva, we tried a new route. This took us to Cortalim, where we stopped to look at the church of St James and St Phillip, built about four hundred years ago high above the left bank of the River Zuari on the site of a Hindu temple destroyed by the Portuguese. It was also the site of one of the first Christian masses held in Goa.

A navigational error brought us onto the highway that led west towards the town of Vasco da Gama. I asked Rahim to stop the car when I saw what lay below the elevated highway. Far beneath us lay a shanty town, Zuarinagar, that resembled, but was much smaller than, that at Dharavi in Bombay. We were very surprised, as little we had seen in Goa led us to expect to find such a miserable looking place. I imagine that it must be visible to the thousands of tourist who land by air at the airport nearby at Dabolim.

After making a few inquiries we found the winding road that followed the palm fringed coast southwards to Colva. That evening, we ate in Colva at Mickeys, an indifferent restaurant, under a canopy upon whose roof the rain battered incessantly.

FRIDAY:

We stopped at Karmali (aka 'Carambolim') on our way to Old Goa. As we approached the large church with its white facade, we heard music and singing, and saw that the church was filled to capacity, or maybe beyond, with an animated congregation. Everyone was waving their hands above their heads and swaying from side to side in time with the catchy beat of the music. The service was being led by a charismatic priest who could not stand still. He ran from side to side beside the main altar, exhorting his enthusiastic flock to sing and dance in praise of the Lord. It was even more exuberant and joyous than a lively musical scene in a Bollywood film! It looked like a manic religious aerobics session. We were spellbound.

A short drive brought us to Old Goa on the banks of the River Mandovi, the first and former capital of Portuguese Goa. Deserted as a result of plague, all that remains of Old Goa is a series of splendid old religious buildings, most of them intact. We made our way through the sultry air to the church of Bom Jesus in which the elaborate cask containing the remains of St Francis Xavier is housed, in a chapel to the south of the elaborately decorated chancel. We set off to walk across the square towards the Se, the cathedral of Old Goa, but the heat and humidity defeated me. We decided to abandon cultural sight-seeing for another meal at the O Coqueiro restaurant at Porvorim. Our intention was to return to Old Goa when we had refreshed ourselves, but our return to that historic site turned out to be less straightforward than we had anticipated.

The quickest way to reach Old Goa from Porvorim involves driving eastwards along the left bank of the River Mandovi from Panjim, a distance of less than ten kilometres. Halfway between the two places, just after passing the church at Ribander, I spotted a small vehicle ferry loading up with pedestrians and vehicles, mostly cars, vans and two-wheelers. My wife made Rahim reverse back to the landing stage, and we boarded the ferry. We had no idea where we were headed!

After about five minutes, having parted with ten rupees for the ticket, we had traversed a stretch of the river and landed on Chorao, the largest of Goa's many islands. Famous for its bird sanctuary which we did not visit, it is a quiet, unspoilt rural place, mostly cultivated as farm land. At first, we had no idea whwere to go on this island, or what to see! Then, my wife said that we should find out whether there was another ferry connecting Chorao with the neighbouring island, Divar. Gerald da Cunha at the Houses of Goa museum had told that this island was worth visiting. There was a ferry, and we reached it soon.

After a short crossing costing only seven rupees (about 10 English pence), we drove off the small ferryboat onto Divar Island. Our idea was to drive across the island to see if there was another ferry that would take us to Old Goa. On the way, we stopped to admire the fine baroque church of Nossa Senhora de Piedade, justifiably highly regarded by the late Maurice Hall whose guidebook we were using. Both its exterior western facade and its interior were splendid. The roof of the small chapel in the nearby graveyard incorporates a part of the ceiling of a former Hindu temple in its construction.

The ferry ride across the Mandovi is possibly one of the best ways to approach Old Goa. The towers and roofs of the churches of Old Goa towering above the forest of palms that lines the bank of the river makes for a fine panorama. It is the sort of view that would have greeted those on board the ships from Portugal as they arrived at Goa's first Portuguese capital. Almost immediately after disembarking, we drove up to the Viceroy's arch built at the end of the sixteenth century. By taking a left turn after passing through this, we were confronted by the facade of the domed church of St Cajetan (apparently, it is the only domed church in Goa). Built by Italian friars in the seventeenth century, this spacious church resembles St Peter's in Rome, but on a more modest scale. It is quite different from all the Portuguese baroque churches that we saw, but splendid nevertheless.

Just inside the grounds of St Cajetan, there stands a solitary arch, the only remaining part of the palace built by Adil Shah, the Moslem ruler who the Portuguese defeated in the early sixteenth century. According to Maurice Hall, this arch is interesting because the lintel above the two supporting pillars that resemble Hindu temple pillars incorporates decoration typical of the Manuelline style favoured by the Portuguese.

Next, visited the Se, the cathedral of Old Goa, is ;larger than any cathedral in Portugal. After viewing this enormous church, we entered its neighbour, the church of St Francis Assisi. Its interior was far more decorative than that of the Se. Nearby, was the church of St Catherine with its simple facade and interior. Having visited four churches in rapid succession in addition to the Bom Jesus we had viewed earlier we felt that we had seen enough of Old Goa for that day.

We drove southwards, beyond Colva, to Benaulim and its sandy beach. Miraculously, the sun was shining, and we were able to sit by the sea enjoying the sun and cold drinks. We watched the sun setting behind the clouds on the western horizon, and then had dinner in Johncys, a beach front restaurant whose tables are arranged under a marquee-like structure. During dinner, the rain returned, forcing those who had decided to dine under the stars (hidden by cloud!) to join us indoors.

SATURDAY:

We arrived in the village of Loutolim to discover that a small street market was under way, and under plastic sheeting supported by wooden poles and guy-ropes. We decided to have a quick look around the market whose wares included clothes, hardware, vegetables, and fruit. Whilst we were there, the skies opened and the rain fell with force and in great volume. Water polled in the folds of the plastic sheeting, and when it had built up enough weight, it fell like a great wave on to those sheltering beneath.

We moved onwards, a short distance away from the village to the Casa Museu Vicento Joao de Figueiredo. Its long facade overlooks the paddy fields beneath it. We had an appointment to meet its current owner Ms Lourdes Figueiredo de Albuquerque, a warm, feisty octogenarian who splits her busy year between Loutolim where she looks after her magnificent home and Lisbon where her family live. The house is divided into two parts, although from the exterior it seems to be one building. The larger and more recent section, chock-full of priceless antiques is where she lives. The other, older part of the house is tastefully converted into guest rooms that are available for hire. These rooms are filled with handicraft that she has made herself: decorative porcelain ware and stitch work amongst other things. This craft is not a sign that Lourdes has little else to do. Far from it, she is still a busy business woman.

During Salazar's rule, Lourdes served a term as a member of the Portuguese parliament representing Goa. She met and spoke to Salazar on several occasions, and told us that she told him what she thought of some of his ideas. The dictator liked her because she was so frank with him. What is most remarkable is that she represented Goa between 1965 and 1969, long after India had taken over Goa from the Portuguese! This is an indication that Salazar and his regime refused to accept that after 1961, Goa was no longer a Portuguese colony. Lourdes told us that when Goa became Indian territory, the archbishop of Goa returned to Portugal, and had little or nothing to do with his former flock. The Goans were unable to appoint a new archbishop until their absent archbishop died twenty years later.

After having been shown around Lourde's amazing heritage home, we returned to Loutolim to see its baroque church before making our way to Raia, where we ate lunch at Nostalgie, a restaurant housed in a traditional Goan house. We ordered far too many of the Portuguese style croquettes on the menu. Some of these snacks looked like the croquettes we ate in Portugal, but often their fillings were spicier than their Portuguese counterparts. The rissoes de camaraes, light puff pastry filled with prawns in a creamy sauce, were not spiced, and very similar to those we had eaten in Portugal. We also had soups at this restaurant including a bowl of caldo verde, a potato based soup laced with thin shreds of special cabbage(?) leaves.

After this delicious but filling meal, we drove southwards to the village of Assolna, where we found, and entered an old church with a simple but beautiful unpainted stone. facade, not mentioned in Morris Hall's guidebook. As short distance away further south we visited the sleepy fishing village of Betul. Being the afternoon, there was little activity, but it was pleasant to look at the boats moored in the palm-fringed estuary of the River Sal. A small ferry across the Sal links Betul and Mobor. Whist we were awaiting the arrival of the boat, Rahim pointed out to me the peculiar crabs scurrying about in the sand next to the landing stage. Each of these smallish, black crabs had one disproportionally large pinkish orange pincer, and scuttled along sideways.

We returned to Benaulim to see the baroque church of St John the Baptist, which we found with some difficulty as the village is spread out over a large area. We returned to Colva where we ate dinner at Pasta Hut, a beach-side restaurant near to our hotel.

SUNDAY:

The town of Margao, one of the largest in Goa, is only ten minute's drive inland from Colva, and is rich in Goan buildings dating back to the Portuguese era. We parked in the square in front of the Holy Spirit Church. In contrast with Wednesday when we first visited this church, the car park was very full. A service was being held, as most of them are, in the Konkani language. The congregation was so enormous that it was not possible for everyone to stand in the church. The overflow stood outside under a canopy over the west doors.

We walked through the rain past a small garden decorated with colourful azulejo tile-work until we reached the long, and impressive Silva house. This, the ancestral home of a Da Silva family, was closed up, and despite ringing on doorbells and knocking on doors we could not find anyone to open it up for us. We made our way back to our vehicle and drove to downtown Margao, where we had breakfast at Longuinhos. This establishment is a café that could have been plucked straight out of any small town in Portugal. Established in the 1950's it retains many features of its original decore ing a cash register which I was told dated back to the day when the café first opened. The fare on offer was very similar to what one might expect to find in a typical café in Portugal today: a variety of savoury croquettes and pastries and a selection (not very large at Longuinhos) of cakes.

A short distance from Margao just off the road to Panjim, after it has crossed the Zuari River, lies the village of Agassaim. After asking directions from several people including a lady who was selling bundles of live crabs at the road side, we found the attractive church of St Lawrence. We were able to enter it easily (i.e. without having to search for a sacristan or a priest to open it up) because a christening service was just ending. The baby was so small and still that it took me a while to realise that she was real, not a doll!

Goa Velha, a small village not to be confused with Old Goa, has the baroque church of St Andrew, which we visited briefly before driving through the rain to the seminary at Pilar. This proved to be a fascinating visit. The baroque church at Pilar was beautiful, and it was there that an elderly man whos spoke good English attached himself to us and became our guide. After showing us around the church and its newer additions including a modern chapel tastefully decorated with blue and white azulejo tiling, he took us to see the final resting place of the bones of the much venerated Father Agnelo De Souza. Whilst looking around the cloisters attached to the church we met one of the Fathers who explained the work of his order to us. The priests trained at Pilar are sent out to do missionary work. Much of this is amongst the tribal people in remote parts of India. They build schools, hospitals and so on. Their main aim is to help these deprived people, rather than to convert them, but on many occasions a few of the tribal people, impressed by what the missionaries are doing, opt to join them and become enrolled as seminarians. Small rooms leading off the cloisters house retired seminarians whose medical needs are catered for by an in-house doctor.

On a hill overlooking the baroque church is the main building of the Seminary, Goa's first missionary seminary. The building that dates back to the 1950's and houses two things that interested us a great deal. The chapel on the first floor is modern but simple. In its east wall there is a modern stained glass triptych made a few years ago by a German artist based on the works of a Goan artist. It depicts St Thomas, St Francis Xavier, and between them Our Lady of Pilar. At the feet of the two saints who helped bring Christianity to India there are depctions of bare headed Hindu saddhus and Moslems with their typical head gear. At the feet of the lady, wonen in saris can be seen. This brilliantly executed series of windows illustrates the religious diversity of India.

The museum on the ground floor of the seminary was full of surprises. There were stones with ancient inscriptions in archaic Indian scripts that dated back to the time of St Thomas when Christianity first arrived in India. A stone carving depicted the infant Jesus in the pose typically adopted in carvings of the Hindu deity Krishna. Instead of holding a flute as Krishna would have done, this Krishna like Jesus held an orb and some other Christian symbol. A large rectangular stone was carved to show, in bas-relief, a Madonna reclining. In this seventeenth century carving she is surrounded by symbols of the Jewish, Hindu, and Moslem religions. The caption to this artefact suggested that this work was supposed to show the harmony that existed in the time when it was carved. Who knows?

In addition to the beautiful carvings, the museum contained a number of other curious things including a large philatelic and numismatic collection. There was a large frame containing pre-World War 2 German banknotes, with a note to the effect that these lost their value with the downfall of Adolf Hitler! Another frame contained a map of Goa made in the sixteenth century by the Dutch traveller Jan Huyghen van Lindschoten. There were many other fascinating exhibits in thsi museum, but I have described the ones that interested me most.

We left Pilar, and drove west of Panjim to the seaside town of Dona Paula. Just as we were examining the market stalls on the promontary that juts out into the bay, the rain fell, and the wind blew with such strength that we could barely stand. We soaked to the skin in seconds. We retreated to a café whose covered terrace overlooks the bay, and ate lunch whilst we gradually dried out. The great thing about the monsoon that whilst it is very wet, the ambient temperature is usually quite high (in the high twenties or low thirties, Celcius). So, one does not fell cold whilst being wet, and drying is speedy.

Near to Dona Paula, on the road leading to Goa's Raj Bhavan, there is an old British Cemetery. It dates back to 1803, during the period that British troops were based in Portuguese Goa as part of an attempt to ward of Napoleon Bonaparte if he had dared to invade India. The last burial in this walled cemetery was made in 1912. I would have liked to have taken a look around, but its gates were locked.

The luxurious and tastefully designed beach resort and hotel, the Cidade de Goa, was nearby. We visited it and looked around the hotel that was built a few decades ago before driving to the Church of Santana in the nearby village of Talaulim. The church was swathed in a matrix wooden scaffolding poles. The poles which must have once been vertical had distorted to produce sinuous curves, which made the underlying structure of the church seem distorted. It was a most odd optical illusion.

Being Sunday, and close to the 26th of July, the feast day of the local Saint Anna, the church was filled to the brim with worshippers. Her feast day, also known as the 'Cucumber Feast', is an occasion when Goans of every religious persuasion bring cucumbers to the church along with wishes that they hope will be granted by the saint. It was difficult to view the church not only because of the service in progress, but also because much of the interior was obscured by the retorative works being carried out. At this point, I want to mention that all over Goa churches of historical interest, however remote, are being conserved and well maintained. I doubt that tourism is the only motive for doing this. It is more likely to be related to the piety of their congregations who use these churches enthusiastically.

Before returning to our hotel, we took a quick look at the Baroque Church at Betalbatim, just south of Colva. We ate supper again at Colva's Pasta Hut.

MONDAY:

We drove from Colva to Panjim, and after crossing The River Mandovi we drove westawards along the river's right (northern) bank until we reached the village of Reis Magos. There, beneath the ruins of a Portuguese fort overlooking the river towards Nova Goa (as Panjim was known to the Portuguese) was the Church of the Three Kings (the 'Magi'). From the porch of this baroque church there would have been a good view towards Panjim had it not been raining. We drove back to Panjim and booked into our well-appointed room at the Hotel Mandovi, before setting off on foot to explore Panjim.

Our first stop was the Goa Public Library, near to the Azad Maidam, a square containing memorials to Goa's liberation from the Portuguese. The vestibule of this library is decorated with azulejo tiles depicting scenes from the 'Lusiads', an epic poem about Portuguese exploration written by Camoes, Portugal's counterpart to Shakespeare.

A short distance across the Maidan, we reached a square on the waterfront. On one side of this is a large building, and one of the oldest in Panjim, the Mhamai Kamat House. This vast residential building that encloses at least two courtyards was the residence of a wealthy Hindu trading family. An elderly man, a descendant of the family, showed us around. Once a single residence, this building that has hardly been modernised is now divided up into appartments, each one of which is occupied by one of the many branches of the original family. This house is next door to another large building, the former pleasure palace constructed Yusuf Adil Shah in 1500. About a century later, the Portuguese modified it to become their Idalcao Palace, the home of the Governor until the new palace, now known as the 'Raj Bhavan', was built near Dona Paula.

We spent some time wandering about the old Portuguese district of Fontainhas, which we agreed could have been part of a typical Mediterranean village, rather than part of an Indian city. We ate lunch in a good restaurant housed in a converted traditional home. After lunch whilst the rest of the family rested at the hotel, I went back to the Mhamai Kamat House to purchase music Cds at a shop housed on its first floor. I managed to find waht I was looking for: recordings of Mando, a musical style developed by Goan Catholics that dates back to the nineteenth century.

In the evening, we embarked on an optimistically named 'sunset cruise' on the River Mandovi. The boat took us downstream past the floating casinos, housed in retired passenger boats, as far as Reis Magos where the relatively calm waters in the estuary meet the turbulent open sea, and then returned. What should have been a serene voyage was marred by the fact that ours was a disco cruise. We had not known until we had boarded our vessel that for one hour we would be blasted by the ship's over powered sound system. Despite this and the occasional showers of rain, we enjoyed ourselves as much as the enthusiastic multitude who had come to enjoy an hour's dancing on the water.

We ended the day by dining in the beautifully maintained 1950s decorated dining room of the Mandovi Hotel. Even though we were talked into buying an overpriced bottle of Goan Port wine, our bill at this elegant restaurant was little higher than at many of the more modest-looking places at which we had eaten in Goa. We retired to bed in anticipation of the fourteen hour drive that we had to make in order to return to Bangalore the next day. The route we chose to take was by way of the port of Karwar on the coast of Karnataka, just south of the Goan border.