Shoreditch Town Hall, 21 March 2014

Sometime in March 1965, when I

was almost 13, I attended a birthday party held by my school friend Hugh Watkins.

After attending a showing of the latest James Bond film Goldfinger

at our local Odeon cinema in Temple Fortune in northwest London , we had afternoon tea at Hugh’s home.

It was at that tea party that I first met the brothers Francis and Michael

Jacobs. They lived next door to Hugh. Michael, who shared his birthday with my

mother, 15th of October, was a few months younger than me. It is

curious that his mother shares the same birthday, 8th of May, with

me.

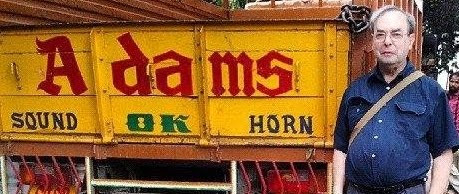

Michael Jacobs (in pink shirt) with Adam Yamey (in white robes and holding a coconut) in India, 1994

Yesterday, 21st of

March 2014, I attended a large gathering to celebrate the tragically short life

of Michael Jacobs. This moving occasion was beautifully organised by his wife

Jackie along with his good friend Erica Davies. His death on the 11th

January 2014 came as a complete shock and surprise to me as I had not known of

his illness. A number of people who had known him for varying numbers of years

shared their memories of this remarkable person at the gathering yesterday. In

this essay, I wish to share some of mine, a few of which derive from an era

before which some of yesterday’s speakers knew him.

Michael was very musical. During

his school years, he became an accomplished clarinettist. He told me that

whenever he went on holiday, he had to carry a mouthpiece with him so as not to

lose his lips' embrasure. His grandmother Sophie was friendly with John Beckett

(1927-2007), a close relative of the writer Samuel Beckett. John was one of the

people who began to re-introduce early music, and its ‘authentic’ performance

into the concert repertoire. Sophie gave Michael and Francis a number of

records that his ensemble Musica

Riservata had recorded. We loved listening to these on the Jacob’s

gramophone, and Michael learnt how to sing some of the renaissance songs. His

renderings of these were superb, and continued to bring joy to his friends

during the rest of his life. One of these, which he sang often, was called El Grillo.

During his later years at Westminster school, both

Michael and I developed an interest in the Gothic and neo-Gothic eras. We were

both interested, for example, in the novels of Walpole and Beckford. He carried this further

by organising a ‘Gothic’ event at Westminster

School

Michael enrolled at the

prestigious Courtauld Institute of Art in about 1971. Very soon, he became

recognised as one of the Institute’s better students. This caused him to be

selected to join a group of academics on the Institute’s highly exclusive

annual overseas excursion. He had to join the tour somewhere, which I cannot

recall, in Europe . It might have been Bavaria . He asked me

whether I would like to join him on a trip through the Low Countries and West Germany on

his way to wherever it was that he was joining the art historical elite. I was

on my university vacation, and it sounded like a good idea. We decided to camp

to save money. I provided the tent, and we set off from London

to Dover , where we crossed the English

Channel .

I was carrying a rucksack with my

belongings and the tent. Michael’s baggage was heavy and unwieldy. He was

carrying not only the clothes and the sleeping bag that he needed for our

camping trip but also things that he needed for his forthcoming trip with the

academics. As this was to be a smart affair with formal dinners, he had to

carry a dinner jacket and its accompaniments including smart shirts, shoes, and

ties. He also lugged an enormous bag filled with huge hard-backed art books

that he felt that he might need for that event. We camped somewhere near Lille in northern France on the first night. All went

well until the following night, which we spent at Grimbergen just outside Brussels . We awoke the

next morning to discover that the rain was falling heavily. Our tent was

soaked, as were our sleeping bags. The rain managed to get into our baggage.

Michael’s books got wet, and his formal clothes became dishevelled. We decided

not to continue with camping, but instead to spend the rest of our trip

sleeping in youth hostels.

Michael guided us to fascinating

museums on our trip. He was somewhat short-sighted, and often went up close to

paintings in order to - as he explained to me - examine artists’ brush-strokes.

This often caused the men and women guarding the works of art to become

anxious. They had nothing to fear from this young man, who was destined to

become a significant art historian and a well-known writer.

When we reached the West German

city of Marburg ,

I told Michael that I had run out of money. The £60 or so that I had budgeted

had almost been spent. There was just enough to pay for my railway ticket back

to London . On

my way back, I had to spend the night in Liége. With nothing in my pocket

except my ticket, I slept on a bench in the railway station. Michael continued

on his way to meet up with the Courtauld party. Despite having had to cut it

short, I enjoyed the journey and Michael introduced me to a lot of art which

was unfamiliar to me. For example, had we not visited the art gallery in

Dortmund, it might have been many years before I might have finally, if ever, learnt of

the existence of the Blaue Reiter

Group and the marvellous expressionist paintings produced by its members.

Some years later in 1982 when I

qualified as a dental surgeon, I learnt to drive and acquired a car. Michael,

who never learnt to drive a car, was grateful to his many friends who were happy

to enjoy his company and drive him around. I was one of them.

In 1984, Michael along with Paul

Stirton published The Traveller’s Guide

to Art: Great Britain & Ireland. The research for this involved a great

deal of travelling around the British Isles . One

holiday, I drove Michael along the south coast of England

and around Wales

so that he could visit museums and galleries in these parts. I had a cassette

player in the car, and played many of the tapes that I had recorded from my

large collection of Central European and Balkan music LPs. Michael enjoyed the

exotic music, and once remarked to me that listening to it whilst travelling

through the British countryside, made the somewhat familiar landscape seem a

little less familiar, even a bit foreign and hence more interesting.

We began our journey along the

south coast at Eastbourne . We arrived there in

the late afternoon. Michael was dismayed to find that its art gallery was

already closed. He suggested that we walk up to the building, and then try to

peer in through its windows. This was unsuccessful; we could not see much

inside it. Undaunted, he approached two young lads walking in the street close

by. He began asking them whether they had ever visited the gallery. I thought

that he was being a little over optimistic; the lads were skin-heads. And, in

those days they were the least likely people to have been interested in art, and were

potentially violent. Fortunately, we escaped unscathed.

During that trip, we celebrated

Michael’s birthday by staying at a better than average bed and breakfast

(‘B&B’) near to Newport in South

Wales . He had chosen a beautiful place to stay. The breakfast that

we were served was one of the best that I have ever eaten in a B&B. Apart

from being offered a selection of different kinds of teas we were served

perfectly prepared fish as well as the usual English breakfast items.

After visiting fine art galleries

in Cardiff , Swansea , and Llanelli, we made a detour to

Laugharne, where the writer Dylan Thomas lived and worked. It was a lovely

spot.

The west coast of Wales

was devoid of places that were deemed suitable for his forthcoming book, but we

drove along it one Sunday. We stopped for the night at an isolated village at

the western end of the Lleyn

Peninsula

Llandudno, which we visited on

the next day, had the most curious museum on our trip. It housed a collection

of carved wooden Love Spoons. I can not remember whether Michael and Paul

included this in their book eventually.

Throughout the trip, and others

that I made with Michael, he was supposed to be our navigator. This was a good

arrangement. He was a good map reader. The

only problem was that Michael had a tendency to fall asleep in moving vehicles.

Whilst investigating the art treasures of southern England ,

he was asleep as usual when we speeded through Cheltenham

and had continued beyond it. Suddenly, he woke and asked me where we were. I told

him that we were almost at Gloucester .

Somewhat panicked, he charmingly persuaded me that we should turn around and

head back to Cheltenham which we had overshot

by almost 10 miles. He had forgotten to tell me that it was supposed to be one

of his stopping places before he had drifted off.

In 1986, Michael published

another book, The Good and Simple Life.

This book about the artist colonies of Europe

at the end of the 19th century also required several chauffeurs during

its research phase. I drove him to the West Country so that he could carry out

field research in the Cornish towns of Newlyn and St Ives. We stayed in Newlyn,

where he was allowed to bring the hand-written diaries of the artist Stanhope

Forbes (1857-1947) from a local library to our bedroom in the B&B. He read

them during the night, and the next morning we sat together for breakfast. We

were the only two guests in the B&B, and we were confronted with a vast

spread of greasy fried breakfast fare. I ate a little of it. Michael ate his

share. Then, he looked at what was left on the table - a substantial amount of

food - and said that we would have to finish it. I told him not to be

ridiculous, but he replied that he did not want to hurt our landlady’s feelings

by leaving it. He was genuinely concerned not to upset her. So, he finished it

off. During the rest of the day, he kept clutching his stomach; his

kind-heartedness and thoughtfulness for others was making him suffer.

I have to thank Michael for introducing

me to St Ives. I have visited this beautiful little port many times since.

Apart from visiting the Barbara

Hepworth Museum

At some stage during this trip,

we stopped, and spent the night at, at Worth Matravers near to Corfe Castle

At yesterday’s memorial event,

the renowned cookery writer Claudia Roden praised Michael’s culinary skills.

This praise was well-deserved. Long before Roden sampled his cooking, I had

been fortunate to have enjoyed many dishes prepared by him in the kitchen that

he had constructed with his own hands in his home in Hackney. His mother was an excellent cook, but he

surpassed her by being both excellent and also successfully ambitious. Few people

could prepare a coulibiak (кулебя́ка) - in essence, a pastry filled

with fish - as delicately as he did for me on at least 2 occasions.

His food was worth waiting for,

and indeed one had to do just that. He would generously invite guests for

dinner, but would arrive full of apologies long after them. The dishes that he

would prepare for us as we sipped aperitifs never disappointed; and that was

not just because we had all becomes so hungry waiting for them. As a cook, he

was a genius. However, occasionally he was a little over ambitious.

This was the case when he decided

to make home-made fresh pasta for a large number of people who were going to

celebrate his 40th birthday at his home. He had decided to make

enough fresh tagliatelle for at least

30 people. I arrived early at his house, and found him in the kitchen cranking

his hand operated pasta machine. Layer after layer of strips of tagliatelle were accumulating on his

kitchen table. To his dismay, he realised that they were beginning to stick to

each other. I suggested to him that fresh pasta needed to be hung up to dry a

bit. So, we separated the ribbons of pasta and hung them over the backs of the

assortment of wooden chairs in his kitchen and anywhere else that seemed

suitable. When that was complete, he had to face the problem of cooking this

vast amount of pasta, and then serve it with his home-made ragu.

On another occasion, my wife and I

turned up at his home the day after he had had a dinner party, at which he had

served his home-made filled pasta. Not only had he made the pasta himself, but

also the delicious filling. The few

leftovers that he cooked for us matched the best tortellini that we hade ever eaten anywhere - and my wife had lived

in Italy

for 4 years.

Michael was blessed with a great

sense of humour. He was very witty. When his brother got married in Ireland , I drove Michael and Jackie to Avoca in Eire , where the wedding was being held. At the reception

after the ceremony, Michael began his best man’s speech by saying something

like: “Unaccustomed as I am to speaking

in public…” then pausing for a few seconds before continuing, “… without being paid.” This had everyone

present roaring with laughter. A few moments later, he continued: “I had originally thought of projecting a few

slides showing Francis’s development from infancy to adulthood, but then I

decided against it. After all, this is a family show…”

Michael’s death has left a gap in

many people’s lives. As the memorial event at Shoreditch Town Hall

Michael Jacobs with Lopa and Adam Yamey at their wedding reception in Bangalore, 1994

I feel privileged to have been his friend and that he was one of the few people who made the long journey from Europe to India in order to celebrate my marriage to Lopa in Bangalore.

+ + + + +

Read about Adam Yamey's writing on: