My

latest book contains tales of Jewish people who migrated to South Africa, and

what they did there once they had arrived.

Now, I want to share with you something of the excitement of how I discovered them.

I will do that by illustrating how I ‘unearthed’ the story of Henry Bergmann, the first of my family to set foot on African soil.

Now, I want to share with you something of the excitement of how I discovered them.

I will do that by illustrating how I ‘unearthed’ the story of Henry Bergmann, the first of my family to set foot on African soil.

My

first forays into family history began in the mid-1990s when I chanced upon a

website dedicated to Jewish genealogy: www.Jewisghgen.org (‘Jewishgen, for

short). It contained a section where, after becoming a member of Jewishgen, one

could register family surnames alongside the towns or villages associated with

them. I entered the only combinations that I knew about at the time: ‘Bloch’ of

‘Barkly East’ (in South Africa) and ‘Yamey’ of ‘Plunge’ (in Lithuania), and

expected little would happen. However, I was wrong. Two days later, I received

an email from Mark in Canada. He was, he informed me, a descendant of the Bloch

family in Barkly East. I checked this was correct with my aunt Manon, who knew his

branch of the, my, Bloch family. Mark sent me what he knew of the Bloch family

tree.

When

I told my uncle Felix about this family tree, he rummaged around and presented

me with something that he said I might find interesting. How right he was. It

was an enormous family tree of the Seligmann family from Ichenhausen in

Bavaria. Very detailed in parts, it also contained some gaps where the

compiler, Reinhold Seligmann, lacked information. I set about updating the tree

using the Internet including web-based Jewish genealogical discussion ‘boards’.

Gradually, I filled in most of the gaps. Whilst I was doing so my wife told me

that although the updating was worthy in itself it was really rather dull. She

suggested that it would be more interesting to try to find out something about

the lives of the people who appeared on the family trees that I was gradually

accumulating. I agreed with her. Here is how I researched one of these people,

the first of my family to set foot on the soil of southern Africa, Heinrich

(later ‘Henry’) Bergmann (1830-1866).

The

Seligmann family tree, which my uncle Felix Bloch gave to me, was a brilliant

starting point for my investigations into the history of my mother’s side of

the family. It shows the descendants of Jakob Seligmann (1779-1843) his wife

Gitl (né Bergmann: 1780-1862) of Ichenhausen in Bavaria. They had five children

of which one was a son. My mother was descended from the son, Isak Rafael, and

also from one of his sisters, Peppi (born ‘Rebekka’). Only one daughter,

Minette, failed to marry or produce any offspring. The four children who

married managed to give their parents many grandchildren, thirty nine of which

survived infancy. Fifteen of these derived from Isak Rafael (1813-1870) and his

amazingly fertile wife Hale (‘Helene’) Springer (1819-1896) from Bamberg. She

was sometimes pregnant more than once within a single year. She had eighteen

children, three of who were very short-lived. The Seligmann family grew

rapidly. Most of Jakob and Gitl’s grandchildren produced several children each.

A

substantial number of the people who appeared in the Seligmann family tree,

which Reinhold Seligmann began compiling in the 1930s, show up in internet

searches because they have done something that has made their names worthy of

being recorded in the domain of public knowledge. I will first concentrate on

the name ‘Rosenfels’ because my communication with of a member of this family,

Marion, resulted in shedding a lot of light onto an aspect of the early history

of Jewish migration to what is now ‘South Africa’.

The

Seligmann family tree shows that Jakob and Gitl’s daughter Klara (1807-1872)

married Lazarus Bergmann (1800-1888), who was born in Dittenheim which is close

to the Bavarian city of Erlangen. Klara’s eldest son was Heinrich (later known

as ‘Henry’ Bergmann). He had a brother Ludwig and three sisters. One of the

sisters, Regine, married Sigmund Rosenfels, and they produced a number of

children including Max Rosenfels (1862-1944), who died in Southern Rhodesia

(now ‘Zimbabwe’). Max, who had been living in Rouxville in the Orange Free

State, took his family by ox wagon to Salisbury (now ‘Harare’) in 1894, where

he worked for the Scot Thomas Meikle (1862-1939) whose firm Meikle Brothers

still serves the citizens of Zimbabwe.

While

I was searching the internet for ‘Rosenfels’, I chanced upon an entry posted by

Marion Rosenfels in Zimbabwe. It was something to do with a school reunion that

she was helping to organize a few years ago. I sent a message to her email

address, wondering whether she had any connection with ‘my’ Rosenfels family.

She told me that she was married to a Rosenfels to whom I am related, and also

supplied me with much interesting information about the family including the

fact that her husband has a cousin in New Zealand, who was working at that time

in New Zealand’s Foreign Service. His name, she informed me, is John. She was

unable to give me any contact address for him. Undaunted by this, I sent an

email to the New Zealand Foreign Ministry.

Some

weeks later, John sent me an email. Along with his friendly message, he

attached a series of emails that had been sent between various departments in

the Foreign Ministry. It was clear from the content of these messages that the

personnel responsible for security were not sure whether to treat my

unsolicited email as the work of a crank or as something that John ought to

see. Fortunately, he received it! Making contact with John had several

unexpected and enjoyable consequences.

John’s

father Robert, who left Augsburg in Germany in the late 1930s, sought shelter

from the Nazis in New Zealand, where he anglicised his surname. He was a

descendant of Klara and Lazarus Bergmann’s daughter Fanny (c. 1840-1913) who

married Nathan Gerstle of Augsburg. Incidentally, John kindly updated his

branch of the Seligmann family tree, and sent the information to me. He also

informed me that he and his wife were about to pay a visit to London, and that

he was keen to meet me.

John

wrote that he and his wife would be staying with his sister-in-law in London,

where she was a senior diplomatic official in New Zealand House. He told me

that she and her husband lived near to us. I wrote back, asking him where

exactly they lived. Serendipitously, it turned out that she lived in our street

at the time, and that he would be staying a minute’s walk from our place. When

we met for the first time, John handed me a spiral-ring bound note book. It

contained over one hundred pages in handwritten German. He said that I could

borrow it and photocopy its contents, which I did.

The

book which he entrusted to me - an almost total stranger - contained his

father’s notes on the history of the Bergmann family. My German is not great,

but that did not deter me from attempting to decipher Robert Lerchenthal’s

handwriting. Soon I will relate what I found most interesting in this personal

history of the Bergmann family, but first I want to provide some background to

my discoveries.

The

Seligmann family tree that my uncle Felix gave me was a copy of another copy

that my uncle Sven had made from the original tree. About twenty or more years

before I became interested in my family history, Sven and his wife met Fea, who

was then living in Camberley. Fea, who was born a Seligmann, was a daughter of

Reinhold, who drew the family tree of the Seligmanns. She allowed Sven to run

her copy of the huge tree through a special copier designed to reproduce

architectural plans.

I

became very keen to get in touch with Fea. The address that the my uncle Sven

had for her was long out of date. So, I posted enquiries about her on

genealogical websites, and also asked my friends Nick and Alice, who live in

Tel Aviv, whether they could find out about her or her relatives (I knew their

names from the family tree and that some of them might be in Israel). My

friends managed to discover the whereabouts of the widow of Fea’s late cousin

who had been a chemistry professor in Israel. At about the same time, I

received an email from Yoni in Israel, who is Fea’s nephew. He wrote to me and

also to Fea, and thus we were able to get in contact.

Fea

and I got on very well. She was delighted to have met yet another member of her

enormous extended family. I visited to her flat in Richmond. She revealed to me

that amongst of her many projects, one was to catalogue and describe the

numerous photographs and records of the Seligmann family that her father had

gathered over the years. Her father Reinhold (1892-1968) had been born in South

Africa in a tiny town called Barkly East. His father Sigmund Seligmann

(1856-1939), who was born in Ichenhausen, went to South Africa where eventually

he set up the equivalent of a department store in Barkly East.

The

material that I received from Fea and John in conjunction with other

documentation enabled me to make major discoveries about Henry (Heinrich)

Bergmann.

One

of the many hundreds of ‘entries’ on Reinhold Seligmann’s family tree, which

caught my eye and aroused my curiosity, was that for ‘Heinrich Bergmann’. It

contained the information that Heinrich Bergman, son of Klara (né Seligmann)

and her husband Lazarus Bergmann: “Gest.

Aliwal-North, Süd Afrika. Verheiratet aber kinderlos” That is:

‘He died in Aliwal North, South Africa. Married but childless’.

Aliwal

North meant little to me apart from the fact that my mother used to tell me

that when she and her siblings went from Barkly East to boarding school in King

Williams Town they had to change trains at this tiny place. I wondered what my

mother’s great uncle Heinrich was doing there.

I

looked for references to Heinrich both in a book about the comprehensive

history of the Jews of South Africa written in the 1950s, The Jews In South Africa, by Messrs Saron and Hotz and also in the

on-line catalogue of the National archives of South Africa (‘NASA’). Heinrich is mentioned in the book as follows:

“…one Bergman, a German Jew, ‘a very great

friend of the De Wet family, associated with all their earliest experiences and

troubles, and who was eventually buried on their farm in 1865’”.

An

entry in the NASA collection lists his grave as being one of those in the

family cemetery of the De Wet family. My interest in Heinrich began to grow,

and was given a boost when I discovered the following passage (translated, in

this case, by my cousin John Englander, and shortened in this article) in

Robert Lerchenthal’s handwritten history:

“The most glittering person - both in the

light side and on the shady side, was arguably Uncle Heinrich. … Early on,

Heinrich realised the opportunity to emigrate to South Africa. I recall a masterly

description of a sailing ship journey, in which he described a mutiny of the

sailors, suspenseful as anything written by a novelist”

The

extract also contained these intriguing words: “… But as he had to pay £5,000, he forged a Bill of Exchange in the hope

that he would have enough money by its due-date. As this was not the case, he

shot himself dead. My grandmother Fanny Gerstle often spoke of him with love

and admiration. She related that all of his friends were horror-stricken by his

suicide, as they would have lent him the money with gladness.”

This

extract fascinated me. The first paragraph of the excerpt reproduced above

contains much that I have found to be true. One evening when Fea was visiting

our flat for dinner, I showed her that passage from Robert’s handwritten

history. She read it without making any remarks. Some weeks later when we met again, she

presented me with a huge folder containing nine or ten large high quality

coloured photocopies. These turned out to be copies of the pages of the letter

mentioned above. This was the letter written by Heinrich Bergmann in 1849,

about which Robert had written that it was: “… a masterly description of a sailing ship journey, in which he described

a mutiny of the sailors...” It contained a lot more, but I will return to

that when I have introduced you to another of my many cousins, the late John E.

who helped me make sense of the letter.

One

of Klari Bergmann’s sisters was my direct ancestor Rebecka Seligmann (1810-1893).

She married Heinrich Wimpfheimer (1813-1876), and both were born in

Ichenhausen. The curious sounding (to English ears) name ‘Wimpfheimer’ both

amused and fascinated me. I knew nothing about this ‘root’ of the family. It

did not take me long to discover that there was a well-documented Wimpfheimer

family from Ittlingen, and that ‘our’ Wimpfheimer family from Ichenhausen had

no known connection with it. By contacting various descendants that were

mentioned on Reinhold Seligmann’s family tree, I began to piece together clues

about ‘our’ Wimpfheimers. Some important clues were embedded in Here am I, the entertainingly written

autobiography of yet another cousin, a portrait artist who had the unlikely

name of Samuel Johnson Woolf (1880-1948). Eventually, I was able to piece

together a family tree of, and much information about, the Wimpfheimers of

Ichenhausen. I published my investigative endeavours and results in Stammbaum,

a journal about German Jewish genealogy that used to be published by the Leo

Baeck Institute (‘LBI’) in New York City.

After

my article was published, I received an email from John E. Retired and living

in the New York Borough of Queens, he worked as a volunteer at LBI several days

a week. One morning, he picked up the latest issue of Stammbaum and spotted my article. He became very interested when he

realised that it was about the very same Wimpfheimer family that his ancestors

had belonged to. This prompted him to write to me, and thus began a wonderful

correspondence between us. I managed to meet him and his lovely wife in New

York a year before he died.

As

I transcribed successive portions of Heinrich Bergmann’s long letter of 1849

from cursive Gothic script into German (in modern Latin script), I sent them to

John, who was born in Germany before WW2 and a fluent German speaker. He made sense of the errors that I made in

the transcription and gradually we translated almost the entire letter apart

from a few sentences on the last page, which were illegible.

Material

contained in Heinrich’s letter contained clues as to what he did in South

Africa, and what brought the earliest Jewish settlers to the country long

before the discovery of diamonds and then gold. My researches continued when we

visited South Africa in 2003. A visit to the small museum in Aliwal North, and

to descendants of Heinrich’s friends the De Wet family produced resulted in me

obtaining even more information about Heinrich. All of this, combined with some

library research including obtaining copies of documents from The South African

National Archives, helped bring a long forgotten name on a family tree ‘back to

life’.

The

genesis of the stories in my book, Exodus

to Africa, derives from research such as described above as well as on what I have

learnt by talking to a number of my relatives who remember much more than they

believed when I first approached them.

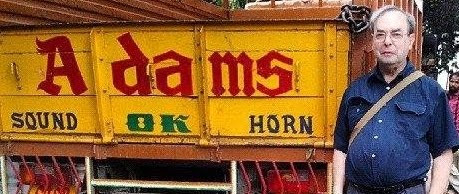

"EXODUS TO AFRICA"

by Adam Yamey

is available in

Paperback (click: HERE )

& on Kindle (Click: HERE)